The Aging of the American Workforce

In times of great uncertainty, we hold fast to those structures which allow us to retain a sense of normalcy. In this time of COVID-19, of quarantine, of vast social and economic disruption, it is the common and familiar events that help remind us that the world goes on. We may not be able to celebrate school graduations or birthday parties as we have before, and our national holidays may not have the customary parades and festivals to mark our observance, but it is important that we observe them just the same.

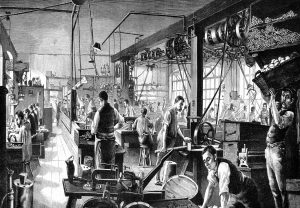

Labor Day has a unique place in our nation’s calendar of federal holidays. The holiday was created by and for the Labor movement to celebrate the achievements of our nation’s workforce and their contributions to the economic, societal, and business successes of the United States. Book-ending our summer, Labor Day marks the transition from the relaxed pace of summertime heat and school vacation to the faster fall rhythms of routine work.

This year, as we all recognize, has been anything but routine. For many, the very notion of returning to our familiar habits of work is impossible, as the pandemic continues to disrupt our nation and endanger the lives of so many people. Particularly at risk is our older workforce, who disproportionately bears the brunt of COVID-19. Often unable to return to work safely, older workers are now in the position of having to choose between the costs of unemployment or ill health. Adding to the trauma is the long-term social isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, where even the hugs of grandchildren can pose a life-threatening risk.

America is, like many other countries, an aging nation with a growing percentage of our population over the age of 55—and as we grow older, so too does our workforce. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that in the next six years “[t]he 75-and-older group is projected to have the fastest growth, followed by the 65-to-74-year-olds.” (Lacey, Toossi, Dubina, & Gensler, 2017). While our popular culture may celebrate youth and “staying young,” we are all increasingly dependent on our older population remaining productive and engaged members of the workforce and economy. While popular culture may portray older people as lacking in vitality (the back-handed compliment of a grandfather being “spry”) or as burdensome on their children (for whom many serve as childcare providers), the reality is that how to successfully retain, develop, and absorb our aging population into our dynamic and fast-evolving workforce will be the greatest economic and workplace challenge of our time.

The reality is that retaining and developing our aging workforce is the greatest economic and workplace challenge of our time.

If we fail to meet this challenge, it will be because of a failure of will and effort, as the older workforce is already a major part of what drives America’s economic prospects. For example, as Joseph F. Coughlin (2017) noted in his ground-breaking book The Longevity Economy, in 2015 the “spending of the 50-plus, combined with downstream effects, accounted for nearly $8 trillion dollars’ worth of economic activity–nearly half of that year’s gross domestic product (GDP).” Additionally, Coughlin reminds us, that the group of 50-plus Americans is growing, moving from 15% currently to over 20% of the population by 2030–only 10 years away (Coughlin, 2017).

That growing—and spending—group is not solely composed of retirees spending their savings on their grandchildren (despite what advertisers often seem to think), but also of an active, engaged, and experienced group of workers who all too often are not considered in labor planning by employers, workforce development agencies, and non-profits. We can and we must do better, and not solely for the older workers–though that reason is sufficient–but for the well-being of all of us. We can start the process by recognizing differences, facing hard challenges, and having hope.

Too often, older workers are not considered in labor planning by employers, workforce development agencies, and non-profits.

Recognize Differences

One way we can do better is to realize that our older workforce is not a monolith. Some members want to continue working in their long-time positions or careers, some want to change pace. For those of the traditional retirement age, nearly 50% will only partially retire, with 26% “unretiring” to re-enter the workforce after initial retirement (Maestas, 2010). Some will continue to work out of financial necessity, some for social interaction and support, while yet others want the structure and routine that organizes their days.

Similarly, their skills are not monolithic. Some will have high-tech skills, others will not. All too often, employers will dismiss older workers with the assumption that they will be lacking in computer technologies or other high-tech skills. This ignores the reality of our face-paced, ever-changing economy in which nearly all workers in the U.S. will need training in new high-tech skills throughout their working life. Our workforce training models and programs need to consider and include older workers as part of their efforts.

Face Hard Challenges

Another way that we can do better is to acknowledge the specific challenges aging workers face and then resolve to meet them head-on in our efforts to recruit and keep older workers working. It is already rare enough for a company, region, or nonprofit organization’s workforce development plan to even consider the challenges faced by older workers. When such plans do so, they often focus on physical challenges (Can older workers lift, stand, stoop?) or skill-based challenges (Do older workers know data entry, phone systems, C++?), but they omit the most pervasive and wide-reaching impediments–structural challenges.

The most obvious structural challenge is age discrimination–the belief that older people are less able, competent, or vigorous than younger people, simply due to their age. These pernicious beliefs are widespread, often reinforced by popular culture, and must be addressed by any well-designed workforce development effort.

But what has become glaringly obvious in 2020 are the other structural inequities that disproportionately harm older Americans – racism, health and healthcare, poverty, and social isolation. The ongoing protests led by Black Lives Matter have laid bare the pervasive evils of structural racism. While the horrifying level of police violence against Black bodies has generally taken the central focus, the movement has also brought national attention to ongoing social and economic injustices, including racial disparities in wealth, wages, employment, housing, healthcare, insurance coverage, and poverty. While these disparities exist across all ages, older Black Americans are particularly harmed by the cumulative effects over their lifespan.

COVID-19 also made evident some of the social and economic disparities that affect older workers. The disease has proven to be exceptionally life-threatening to older people, which meant months of self-quarantine became necessary, intensifying social and physical isolation and amplifying disparities in health, wealth, access to food, housing, and societal infrastructure (CDC, 2020).

For workforce development groups to take a leadership role, they must attack injustices directly.

For workforce development groups to take a leadership role they must attack the effects of these injustices directly and to recognize their intersectional impact. Older Black workers are at increased risk of getting sick and dying as a result both of age and race. Any attempts to serve this population and ensure their place in our workforce must be prepared to offset these inequities directly and not to assume that if one aspect is being addressed (that is, race or age) that will suffice for those workers who are disadvantaged from the effects of both.

Have Hope

In the face of these disparities and inequalities, one of the most powerful things we can do is to have hope. One of the most powerful ways to do that starts with recognizing the reason we have an aging workforce: we are living longer—and healthier—lives than at any time in human history. We have begun to rethink what the decades mean—where our great-grandparents may have felt old at 50, we might not feel that way until 80. As Baroness Camilla Cavendish puts it, “In England, the proportion of over-65s with any kind of impairment has been falling for two decades. In America, three-quarters of people under 75 have no problems with hearing or vision, no difficulty walking, and no form of cognitive impairment. These are fully-fledged citizens with plenty left to offer, not retirees on their way out.” (Cavendish, 2019). Our increasing lifespan means that by 2024, nearly 25% of our workforce will be over the age of 55, and nearly 30% of people 65-74 will still be working (Buckley & Bachman, 2017). The reality of the demographics means that the case for including older workers is already made.

As Camilla Cavendish writes in Extra Time, older American workers, ‘are fully-fledged citizens with plenty left to offer, not retirees on their way out.’

This isn’t a small group whose costs of inclusion outweigh the return on investment, this is the demographic that must be included if you want your business—and the economy—to thrive. To quote Field of Dreams, “if you build it, they will come.” Those forward-thinking enough to provide opportunities to older workers can be confident that there is a workforce ready to step up.

We can also take hope from the fact that we are not alone, nor will we have to re-invent the wheel. Many other countries are aging as well. Japan, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Sweden, among others, all have larger percentages of people 65+ than the U.S. and are all trying to figure out how to address this unprecedented shift in demographics (Coughlin, 5-6. Also, Cavendish, 71-99). We can learn from the experiences of other high-income countries that are experiencing this aging wave now.

Finally, we can take hope from the ability and tenacity of America’s business people, academic institutions, civic bodies, and a diverse and vibrant workforce. Our technology sector thrives on disruption and new ideas. Our economy—while wounded by the impact of COVID-19—is still the largest in the world. We have the talent, the ideas, the infrastructure, and the money needed to ensure that older workers remain a valued—and valuable—part of American prosperity, but we must have the leadership, the far-sightedness, and the will to see it done. I hope you will join me in that effort.

We need the leadership, far-sightedness, and will to ensure older workers are a valued – and valuable – part of our labor force.

References

Buckley, P. & Bachman, D. (2017). Meet the US workforce of the future: Older, more diverse, and more educated. Deloitte Review, 21(July), 46—61.

Cavendish, C. (2019). Extra Time: 10 Lessons for Living Longer Better. HarperCollins.

Centers for Disease Control. (July 24, 2020). Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

Coughlin, J.F. (2017). The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing, Most Misunderstood Market. PublicAffairs.

Lacey, T.A., Toossi, M., Dubina, K.S., & Gensler, A.B. (2017). “Projections overview and highlights, 2016–26,” Monthly Labor Review, October. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2017.29.

Maestas, N. (2010). Back to Work: Expectations and Realizations of Work after Retirement. The Journal of human resources, 45(3), 718–748. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2010.0011